Changing language in the #climatecrisis

#languagematters

Welcome to my new Substack, called 'Changing language in the climate crisis'. I am an Associate Professor of Linguistics, based at Macquarie University in Sydney. You can find my academic profile here. I will be posting fortnightly, with a post coming on a Monday morning.

I'm worried my Substack title is not catchy enough. But you gotta love its ambiguity. Is this newsletter about how language is changing because of the climate crisis, or about how we should change language to respond to the climate crisis?

The grammatical trick is that 'changing' can be interpreted either as an adjective or a verb, depending on your grammatical POV. I want both.

Changing (adjective) language

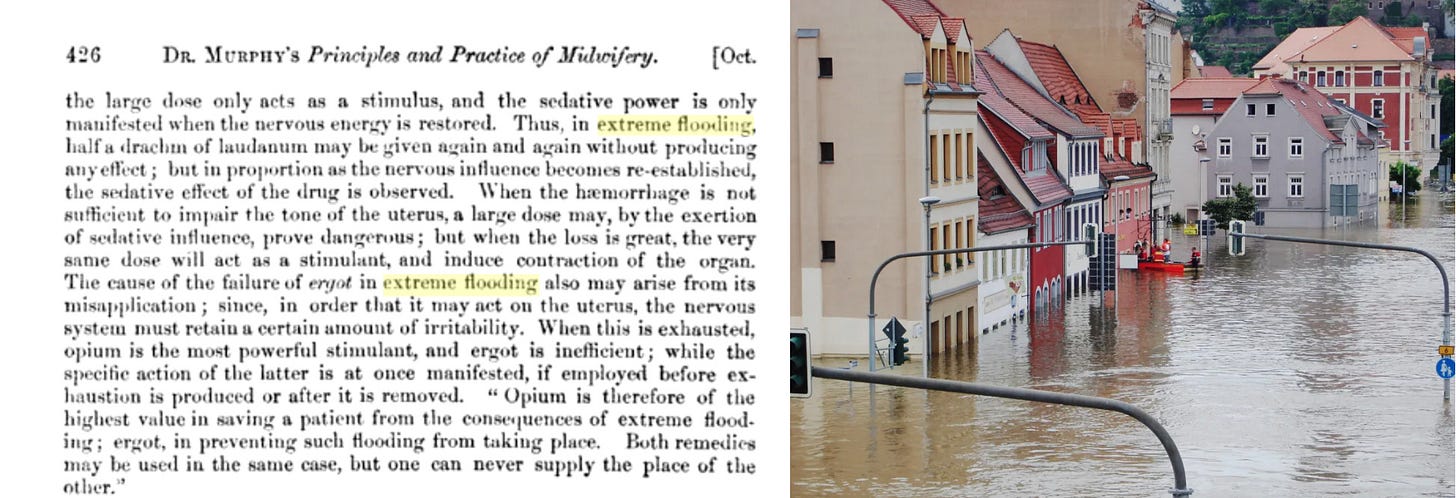

Interpreting ‘changing’ as an adjective, I want to explore what new words are coming into our language to help us understand the processes and impacts of global warming. Words like ‘extreme flooding’, once a term used in 19th obstetrics for the potentially lethal loss of blood that some women suffered in childbirth, and now in the 21st century describing the deadly flooding that many people of the world have witnessed in their homes and neighbourhoods. The first was treated with opium; the second will only be cured by stopping dirty fossil fuels.

‘Extreme flooding’ in the 19th century (left) and the 21st century (right)

Or how about the concept of ‘solastalgia’, which like ‘selfie’ and ‘budgie smuggler’ is an Australian coinage. Barely 20 years old, the word captures the feeling of nostalgia for the home and place you have lost even though you haven’t left. It’s not in the dictionary yet, but as more and more of us come to terms with climate grief, we will be reaching for this precious word.

‘Changing’ language (verb)

Interpreting ‘changing’ as a verb, I want to write about how we can change public discourse so that action on climate becomes easier to take. We need to change the linguistic climate around global warming, so that taking action on climate is not an act of resistance, but what all of us, led by governments, business and civic society, have to do.

We need to think about our key messages - what to call the people who are working very hard to keep digging out or pumping up dirty fossil fuels? Climate deniers? That’s way too nice. Or how we talk about CO2, a polluting, heat-trapping gas that we described as ‘emissions’. Some of our most neutral and ‘scientific’ looking words carry a dagger in their back pockets.

To change our dirty fossil-fueled reality, we need to change language, and that means putting words out into the world and getting them on everyone’s lips. Who knows? Maybe together we can invent some news words to help us understand our heating world and how to change the way we think about it.

The science of climate is settled. The problem now is one about communication. We need to understand better what fossil fuel companies have known very well for a long time - how words shape meaning and minds. We need to get ahead of the game, to make sure a pro-climate narrative becomes the dominant framing for the way we see the world now and into the future. We need to think about the key words that open people’s minds to the problem and its many solutions. Then we need to get these words onto everyone’s screens and into their heads.

Words and minds

There is evidence that more people understand our planet is warming and that serious impacts are here already or well on their way. The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication produces a regular report called the 'Climate Change in the American Mind', based on a national survey of about 1000 adults. The latest results (from surveys conducted in October 2023) show that the Americans who think the planet is warming outnumber those who don’t by a ratio of nearly 5 to 1. More than 40% of those surveyed agreed that people in the US were already suffering the effects of global warming. Seventy percent believe global warming will harm future generations.

Despite the scale of the issue, most respondents reported very little day-to-day exposure to discussions of climate. Sixty-five percent ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ discuss global warming with family and friends. Twenty percent report hearing people they know discuss global warming once a month or more frequently. About 10% of respondents reported feelings of anxiety or depression due to fears of global warming.

The ideas Americans or anyone else have in their minds are not random or accidental. We don’t say things because it’s just what we happen to think - we think them because it is what we say, or what we read or hear in our little slice of the universe.

We have ways to measure the likely exposure that someone will have to a way of wording and thinking about the world. For instance, we can look into large data sets of news, a crucial source of (dis)information about climate. We can, for instance, find out the frequency in our news of the term ‘global warming’ versus ‘climate change’. In 2010, ‘global warming’ was just under half the frequency of ‘climate change’. In 2023, the news was nine times more likely to opt for ‘climate change’ over ‘global warming’1.

If you think it doesn’t matter what we call this existential crisis we are confronting, check out this 2013 study, also by Yale Climate Comms researchers, about how differently people feel when they are surveyed about ‘climate change’ versus ‘global warming’. The term ‘global warming’ produced greater certainty that the phenomenon was real, was caused by humans, was a source of threat to future generations, and generated a greater willingness to take action. Meanwhile ‘climate change’, as one respondent reported, just feels like you are going ‘from Pittsburg to Fort Lauderdale’.

No wonder George W Bush, the first US president of the 21st century, was advised to use the much calmer, more neutral term ‘climate change’ and to avoid talking about ‘global warming’. And the evidence is that he took this advice.

Yeah, #languagematters.

Let me know what you think about this first post out in the world. I’m keen to hear your linguistical questions on language and climate and warming, what words you think are useful, and the ones that you think are Machiavellian. There’s plenty more where this came from - stay tuned :)

Fun footnote: you can check my figures by going to the same data, hosted at the english-corpora.org website, and selecting the News on the Web (NOW) corpus. And a shout out to Professor Mark Davies, of Brigham Young University for this amazing data set. The measure in my graph is ‘words per million’ (wpm), i.e. how many times in a set of million words of this news data do you run into ‘global warming’ or ‘climate change’. It’s a standard measure used in corpus linguistics.

thanks. so often feel that grief, and a lack of any control over what is happening. the solastalgia is big in me...

look forward to more.

Hi Annabelle, congratulations on your new Substack. I love the title and the way you have taken us on a ‘changing’ journey - adjective and verb. I too, enjoyed reading about the history of the term ‘extreme flooding’. Looking forward to learning more. 🙏