Being native to now

'Bucket list' is out - 'ruggedization' is in

I’ve been trying to find the right words for the kind of rebirth I’ve been going through to understand what it means to be living in the climate crisis. Like here and now. Each day. I remember the feeling in my head when I realized the climate crisis wasn’t waiting to arrive, it was already here. It was a weird experience - what I thought was something sitting in a somewhat distant future came crashing into today.

And now I’ve finally discovered the concept that explains this feeling. It’s called being ‘native to now’. And that sense of time suddenly collapsing into itself - it also has a name. It’s called The Snap Forward, and like the expression ‘being native to now’ it’s author is Alex Steffen. Somehow I stumbled across a two year old newsletter post of Steffen’s, and I finally got a label for my feelings of being a stranger to these times, the feeling that time itself is a bit wibbly-wobbly and timey-wimey.

Steffen’s post is titled ‘Old Thinking Will Break Your Brain’.

Alex is a futurist. He has written books about the planetary crisis. The ‘old thinking’ he warns us about looks like this:

We grew up in societies built upon certain assumptions about how the world works, and how the planet around us should be seen. We now know those assumptions were wrong in profound ways, and in one human lifetime we have altered the climate and biosphere, squandered vast natural riches and destabilized a myriad of systems we depend on. We have made the circumstances of our lives discontinuous with everything that came before us. The societies we live in are now catastrophically unsuited for the planet we’ve made. Yet we still see the planet around us with worldviews formed inside of those societies.

Old thinking is going to run its course: sooner or later, the physics of climate, still ignorable now thanks to a highly sophisticated propaganda machine, will take charge.

The little life I live inside is full of old thinking and old thinkers. I can spend whole days where not a single person mentions climate. Many of my academic colleagues continue to plan their academic lives as if the old world is still here - travelling half-way around the world to attend face-to-face conferences where climate, if mentioned, will be allocated a minor space on a program full of business as usual. As if the need for a rapid transition doesn’t include the CO2 of the flights we take. The problem is in another time and place.

When you have snapped forward, and starting being native to now, you can see how much the present is stuck in the past because it thinks the old future is still with us.

We didn’t used to have the future

Our everyday conversations are powered by our modern grammatical habits. As speakers of modern English, these habits includes lots of grammatical and lexical options for constructing the future, for indulging concepts of uncertainty or probability, and for living in very vague or ungrounded spaces and times.

We didn’t use to have the future. Rewind to our foreparents who spoke Old English - a.k.a. Anglo-Saxon - when English had only two verb tense options: one form of the present, and one form of the past. As Millward notes in A Biography of the English Language, Old English did not have the rich and complex verb tense system we live through today - all the various options that allow us many ways to slice and dice our experience of time. This grammar of English (which I rely on for much of the work I do) describes 36 different options in the the modern English tense system.

An Old English speaker could not have said ‘I would have wanted to go’ or ‘I have been thinking about you’. And Old English speakers did not, could not yet say, ‘The heat will kill you first’, the title of Jeff Goodell’s 2023 book. Neither, in another version of projecting the future, could they have said ‘the heat is going to kill you first’. This form of the future, based on what we call the present continuous tense, was not yet ‘invented’.

Instead, Old English grammarians explain the ‘future-y’ stuff in Old English was managed by some combination of adverbs, and, like everything else in language (pace Chomsky), by context. It was at the end of what linguists generally consider this phase of the history of English, we can begin to see forms emerging that will become our ways of expressing future time: the rise of verbal auxiliary ‘will’, and of the ‘present continuous’ form, for example ‘I am going’.

Being able to live in the future was something that had to emerge over time. The English word for ‘future’ was not in the Anglo-Saxon’s vocabulary - the Oxford English Dictionary attests it to c.1374, just a few years before Chaucer began writing The Canterbury Tales in the version of English we call Middle English. It takes the turn of another century for the word ‘forecast’ to emerge (1413), while the now very pervasive concepts of ‘goal’ and ‘plan’ are creatures of the 16th and 17th centuries. As for ‘key performance indicator’, of course that is the child of the late 20th century, as is the concept of a ‘bucket-list’, that list of things you have to do before you die.

How the climate predators weaponized the future

Now we have supercharged ways of looking into the future, of imagining what it will look like. We spend a lot of time now planning ahead, churning out ‘goals’ and ‘kpi’s’, living in or for tomorrow, compiling our ‘bucket list’ of the things we want to do before we die. One of the top hits if you google ‘bucket list’ offers 220 bucket list ideas. Many of the top 20 on this list involve consuming high carbon polluting products: ‘Visit New York for Thanksgiving Day Parade or New Year’s Eve!’. ‘Eat shark in Iceland!’. ‘Visit the sand beaches of Hawaii, Galapagos, Indonesia or the Dead Sea!’. ‘Touch six out of the seven continents’. The list goes on.

This modern penchant for living in the future is just one more thing that the fossil fuel industry has used to stop people seeing that the climate crisis has already arrived. They have weaponized the future. And thanks to language, they have done this effortlessly. The evidence can be found in this brilliant paper, by Professors Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes, about how one of the big oil companies, Mobil, then ExxonMobil, polluted public discourse through a 30 year strategy of deceptive marketing.

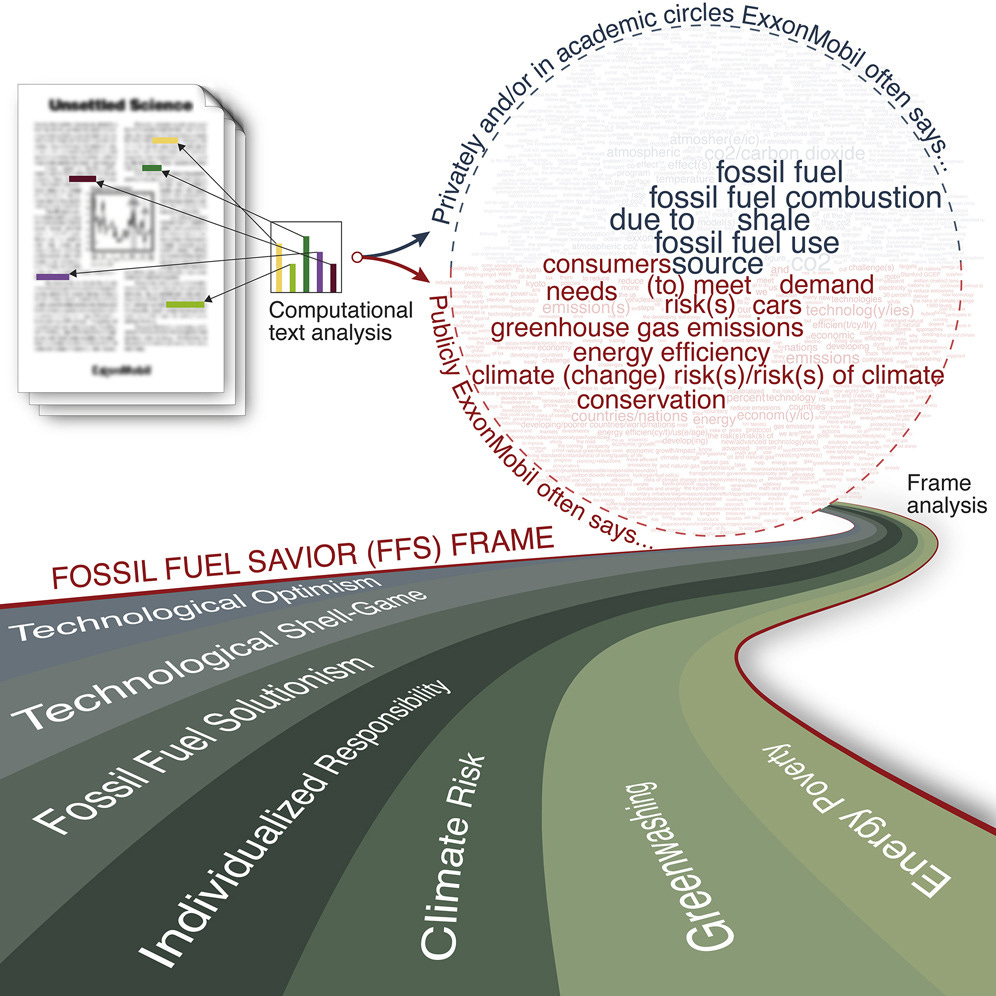

This strategy included the use of paid advertorials in The New York Times, that is, content that appeared as if it was an article, but which was paid for by the company, invisibly promoting their point of view - thanks NYT (:. The researchers analysed all advertorials paid for by this company which took some position on anthropogenic global warming between the years 1972 to 2009. The researchers conducted ‘frame analysis’1 - a common research approach in the study of media, where patterns of language in text can be seen to solidify around some overarching themes. This analysis resulted in identifying dominant frames or ‘topics’ in this data.

Graphical abstract for Supran and Oreskes paper

One of these topics involves relating climate change to the concept of ‘risk’. These researchers show that as we enter the 21st century, with the science of climate becoming clearer and more widely known, these advertorials build a narrative around climate ‘risk’. While ‘risk’ sounds like a negative thing to be raising in relation to climate, its covert power is to shift a problem out into the future. The researchers, Supran and Oreskes call this practice ‘discursive grooming’ - as far as I know it is a term they have invented. As the authors note, drawing on risk rhetoric is helpful for casting doubt on the effects of global warming, and for subjecting it to ‘temporal discounting heuristics’: in other words, for making us think that the problem is not here and now, but something that might happen in the future.

Like sexual predators who groom potential victims, these climate predators have seeded public discourse with covert messages designed to groom us so that we are vulnerable to the ways they wants us to think about the climate, energy and fossil fuels.

Snapping Forward

What does ‘native to now’ look like? I can only tell you my version of it - I think about climate all the time, and I’m constantly calibrating the realities I hear around me against what I understand to be both already here, and coming towards us. Another term being used is to capture this idea is being ‘collapse aware’,

I try to imagine what everyday conversation would be like if everyone lived like we were in a climate crisis. One thing I imagine is that we would all know, all the time, the estimates of CO2 concentrations in our atmophere. Instead of talking about how many steps we have done this week or month, we would be discussing the newest numbers from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii - and we would follow these numbers in the ways that we all tracked rising COVID numbers as the pandemic unfolded.

We would all expectantly wait for the montly numbers - we would all know that figures for January 2025 are an almost 4ppm rise on the same time last year. Friends would greet each other with statements like ‘did you see the new numbers from Hawaii?’. I haven’t yet had a single conversation on this month’s planetary-defining number.

Source: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/

And there would be no more conversations about ‘bucket lists’ - instead, I would be having conversations with at least some of my friends and family about where to live as climate impacts worsen. Some of us might even sign up for Alex Steffen’s ‘personal ruggedization’ crash course - the next one is starting shortly. We would be talking and thinking clearly about the ways our natural systems are shrinking and collapsing, and what that means for us and our families. We would be talking, constantly, about how to talk about the future with our children. If you are looking for help, check out this Climate Kids video from Melbourne University’s Climate Futures.

I can only recall one single occasion of talking with a small group of friends about what their kids understand about their future prospects as we keep on burning fossil fuels - the conversation was tentative and conducted in hushed tones. We all knew how confronting this territory is, and we all quickly changed the topic.

I also imagine we would all be talking more about ways to live more simply - taking ideas for instance from writers like Jodi Wilson, writing Practising Simplicity. While being more honest in our conversations about the climate crisis, we would also share the joy to be found in living a simpler, less polluting and extractive, life.

For a bit more info on this method, which is based on a form of topic modelling referred to as ‘LDA’. As they explain: ‘LDA is a computational, unsupervised machine-learning algorithm for discovering hidden thematic structure in collections of texts.253 A priori coding schemes are not supplied. Rather, ‘topics’ (clusters of words associated with a single theme) emerge inductively based on patterns of co-occurrence of words in a corpus.

Thanks for the video link Annabelle, keen to watch with the kids. I enjoyed the walk through history and tenses. Lots to ponder. Interestingly, there is a big focus at my children’s school on etymology and word origins, perhaps with this knowledge coupled with creativity and a sr as of community they will come together with some great ideas for the future. One can only hope.

Woah! No language for future orientation… mind bending. Being Native to now is a lovely way to draw our attention to the present, freed of the baggage of the past. Thanks!