Among many great Gershwin and Gershwin tunes is the one that draws attention to small differences in the pronunciation of English words:

You like potato and I like potato

You like tomato and I like tomato

Potato, potato, tomato, tomato

Let's call the whole thing off

The song rattles off a few more examples, with contrasting pronunciations of words like ‘either’ and ‘neither’, ‘laughter’ and ‘after’, ‘Havana’ and ‘banana’, returning again and again to the refrain to ‘call the whole thing off’, which is intertwined with the sneaky counter lyric to ‘call the calling off off’. Here’s the version with Fred and Ginger, tap dancing on roller skates. I know right.

The song produced the expression ‘tomato tomahto’, which the urban dictionary defines as ‘a difference between two opinions that is so small that it doesn’t matter’.

I get this song. It is fun and frivolous. But even though the sound shape of a word is arbitrary - any sound will do to make a meaning, a fundamental principle of language which makes it open and infinitely extendable - the differences we see in how words are pronounced isn’t arbitrary or meaningless. It shows where you come from, and where you come from can include your social class. Do you sound like someone from the ‘wrong side’ or the ‘right side’ of the tracks? You can even hear these distinctions in the Gershwins’ ‘Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off’ pop song.

The point is, language rarely offers you a difference in expression or wording that doesn’t come with some kind of value, whether it is in accent or in the choice between words or expressions. In fact when a word has lots of synonyms, this means it is a concept that is culturally significant. So small variations in meaning are ‘lexicalised’ - i.e. put into words. A good example is the many words we have to suggest and stigmatize a woman who has apparently had more than her share of sexual partners. Women’s bodies are public property, and the florid lexical variations we have in English for the term ‘slut’ are one of many indications of this public status.

The ‘presence of absence’

It is burden to realize that each and every word you choose might have been different, that there’s almost always another option that you might have chosen instead. It makes you want to call the whole thing off.

But as I love explaining to my linguistics students, language encompasses a weird paradox where it gives you choices, but then it makes you choose. While allowing us freedom to choose, language defines what the options are, and makes you pay a semantic price for whatever choice you make. Each word you choose is unconsciously processed by your audience against the background of what you might have said instead. If you interested in the linguistical terminology, I’m describing what one of the many parents of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure, describes as the ‘in absentia’ relations - the words and meanings in the background that enable the word you choose to be meaningful.

Professor of German and Linguistics, Thomas Christy, called this phenomenon ‘the presence of absence’. Every word you choose comes with the baggage of the words you could have chosen, like haunting ghosts in the shadows of every word. These unspoken words have to be there in the background, because without them the word you choose won’t work.

And there’s more to what seems like a simple process of selecting a word from the options available. From the 50 years or so of studies in corpus linguistics, as well as the work of linguists like J.R. Firth writing even before we had computers and large data sets, we know that words tend to cluster. As Firth’s very well known expression encapsulates, ‘you shall know a word by the company it keeps’. Choosing one word over another is predictive of the other words you are also likely to choose.

No pressure here - but what I am saying is that every word you choose comes with hidden baggage, and it makes you more or less likely to choose other specific words. The act of choosing a word, which we do unconsciously most of the time, is like Fred and Ginger tap dancing on roller skates - complicated, but we do it without even having to think about it.

Emitters or polluters? Let’s call the calling off off.

I’m not suggesting you stop and think about every single word you choose. Frankly you won’t be able to do anything at all ever again if you tried to do this. Language is just too complicated, which is why it is so powerful. But we can choose to focus our minds on some of the most important word choices we make. This will feel ‘effort-ful’. Making your brain stop and think before it put words in your mouth requires a bit of focus and attention, because language works by rolling off our tongues.

In the battle over our planet, climate communicators are in debate about what is or isn’t strategic. Here’s a quote from Bill McKibben’s latest post at his must-read Substack The Crucial Years. The post is titled ‘Fear’, written when the ‘tightly coiled ball of physics we’re calling Hurricane Milton’ was on its way across the Gulf of Mexico and Bill could not sleep.

We’ve spent some time in recent years worrying that there was too much fear-mongering and doom-saying in the way we talked about climate change—that it was wearing people out. And indeed there’s truth there—if we’re going to do what we must, the story in the years ahead needs to be as much about the adventure of turning our planet solar as the dread that we’ll turn our planet Venus.

But I think we can all agree that the behavious that are critically endangering our planet - the ongoing burning of dirty fossil fuels - have to be made visible, and have to be stigmatized. We have to ‘de-normalize’ burning fossil fuels, because we now need everyone to see, clearly, that these dirty fuels are just not compatible with a livable future. We need everyone to understand how dangerous it is to continue to pollute the atmosphere with CO2 and other planet-heating gases. And in this process, we need to choose some of our words strategically.

I recently came across this excellent explainer, published by CNN in January this year. It grabbed my attention because it put the word ‘polluting’ into its headlines, and even used the term ‘climate chaos’.

This language is ballsy (apologies for the sexist metaphor) - I have the data to prove it (see below). There are options of course - to use the language of ‘emissions’, and ‘emitters’ instead of ‘pollution’ and ‘polluters’. I think you’ll agree that the word ghosts that go with ‘emit’ are very different from those that haunt the word ‘pollute’ - ‘emit’ just doesn’t feel that serious, while ‘pollute’ has irretrievably negative connotations. While the CNN article didn’t completely avoid references to ‘emitters’ and ‘emissions’, the writers were committed to a very strong textual prosody (that is, a recurrent favouring of some words) of ‘polluters’ and ‘pollution’. For example, the article explains that in 2022, China was ‘the largest climate polluter’. For a wider context, and with the use of some very clear and attractive visuals, the article explains:

Most of the world’s planet-heating pollution comes from just a few countries. The top 20 global climate polluters — dominated by China, India, the United States and the European Union — were responsible for 83% of emissions in 2022.

As this quote shows, not only do we get clarification that CO2 is polluting our atmosphere, but that this pollution is ‘planet-heating’, a term that helps explain to a non-scientific readership what scientists tried to capture with the term ‘greenhouse gas’. For scientists it is term to explain how some gases create conditions that heat up our planet. For ordinary folk, we see some beautiful plants grown in greenhouses. ‘Planet-heating gases’ needs to replace ‘greenhouse gases’, because is a simple concept that directly explains the effect of burning fossil fuels.

As I’ve written about before, the frequency of a word or expression is a very important part of how it means. High frequency words underpin our dominant reality, because these words feel as if they explain the world ‘as it really is’. If everyone says ‘carbon emissions’, then this becomes the default reality, and variations on this theme draw attention to themselves, like showing up in pink at a funeral. But no word is neutral. The problem with trying to challenge majority views is that the new wording stands out at first. Its users come across as if they have an agenda. But the more we add our voices to raise the alarm, the more we can tip the balance in the planet’s favour.

What this practically means is we want more people on board with a few crucial strategic words and wordings, that send a constant message about the dangerous planetary impact of continuing to burn fossil fuels. We need to step up our game with a few key words, like ‘climate pollution’, ‘big polluters’, ‘planet-heating gases’, and ‘planet-heating pollution’ - as you can see in the CNN article.

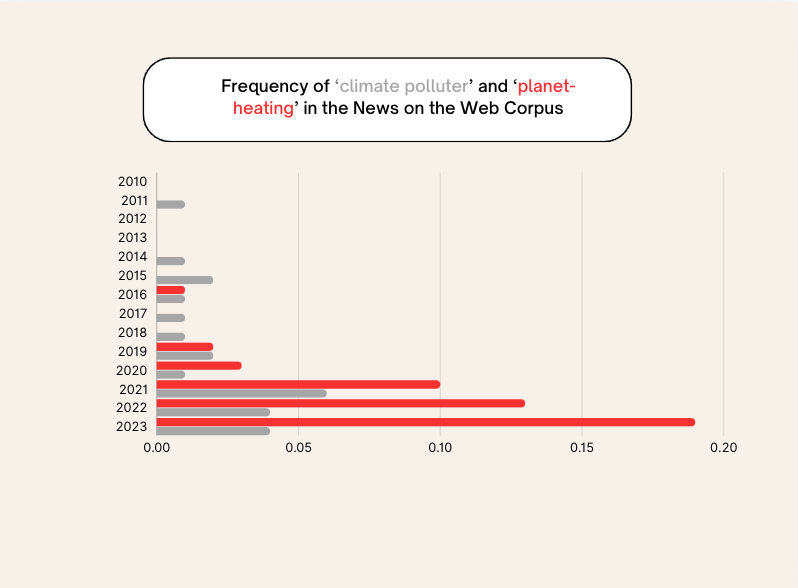

When you start using this language, people will notice. Even more than saying ‘tomato’ when everyone else is saying ‘tomahto’, if you say ‘planet-heating pollution’ while most people are still saying ‘carbon emissions’, you’ll stand out in the crowd. But if we all just keep going, this language will spread. The graph below shows the very small, but rising frequency (using the frequency measure of ‘words per million’) of the word ‘planet-heating’ in the News on the Web (a big data set of English news from 20 countries, from 1/1/2010 until yesterday); and the expression ‘climate polluter’ starting to make its way into news reporting.

Shout out to Laura Paddison at CNN

The figures in my graph help explain why I noticed this article from CNN. The language of its writer Laura Paddison (so ably assisted by Annette Choi’s fantastic graphics) jumped out because expressions like ‘climate pollution’ and ‘planet-heating’ are still low in frequency, as the evidence from this graph shows. We need to keep it coming, keep on repeating it. We need to call the calling off off, to keep tap dancing on our roller skates as we try to change the way we word and think about the pollution heating out planet. We have to do our best to turn the established, highly polluting fossil fuel burning practices into behavours we recognize as dirty and very very dangerous.