Dear Dr Robinson,

I wonder if it is OK to call you Stan?

Bri Lee, a writer I admire very much, invited a small group of fellow Substackers to pen a letter to an author of a book which changed our lives. Bri was prompted to do this after receiving a letter from one of her readers, about her book Eggshell Skull that has changed many lives. This reader got the frontcover of Bri’s book tatooed on her back. In turn Bri penned her own letter to a life-changing author, Maggie Shipstead, who wrote published Great Circles in 2022 - a book that gave Bri a striking clarity about ‘the entire shape’ of her life.

Is there a greater satisfaction for a writer? To give to your reader the kind of clarity that clarifies the. whole. shape. of. their. life.

I’ve read a few great books in recent years. But when Bri invited me to #WriteAWriter it was your The Ministry for the Future that came immediately to mind. Your book came into my hands through the agency of beautiful young person in my life. Browsing in Melbourne’s Readings bookshop on a summer evening, this family member, who is deeply interwoven into many aspects of contemporary political struggles, found and bought me the one copy then in the store.

The Ministry is a book whose cover I opened with trepidation. A book that I could not read before going to sleep. A book whose effect was so profound on my thinking that it also gave me clarity on the shape of my whole life.

The book has been described as a ‘history of the future’ - we travel in your little time machine to a very near future constructed through voices we can already experience in the present. The book is so narratively courageous. We have two central characters: Frank, a climate disaster survivor with PTSD, and Mary Murphy, a former Irish Foreign Ministry leading the UN’s Ministry for the Future. Their paths inevitably cross, each providing to the other a perspective that shapes their character arc. The characters move through key dramatic events, but these are combined with ordinary life experiences which are essential to scifi - or ‘cli-fi’ as it is now called - being relatable.

Interspersed with the novel’s narrative are many short, sharp chapters from un-named voices, in third or first person, which fill out the very modern drama of living in apprehensively, portentiously, apocalyptic times. Chapter 2, barely 6 lines, is a first person narration by the sun. Chapter 11 is less than a page, and begins with a dictionary definition of the concept of ideology. Chapter Chapter 20 pauses the narrative drama of our emerging protagonists to explain the Gini coefficient and other measures of wealth disparity - we know the burden of climate crisis is being unequally shared. In chapter 48, the un-named first person narrator tells her story as a climate refugee inside a wired encampment. This patishe mode felt like a writerly exploration of the Gaia principle - that living and non-living beings and things are synergistically interconnected. Everyone and everything is part of the story you tell in this novel.

Reframing time and space

The book has had a life-changing impact on me, by no less than upturning and reframing my relationships to time and space. In terms of time, the book left me deeply aware that the climate crisis is here and now. I had to learn that from fiction, and from a novel ostensibly set in the future. Your fictional future put me much more solidly into the present. It was chilling to read about an imagined future in your book when it has already arrived. Your novel starts with this sentence:

It was getting hotter.

I read the opening sentence of this fictional future in the early months of 2022. In your book, an American in an ‘ordinary town’ in Utar Pradesh, working for an NGO, is busy living through and witnessing an horrific and traumatic heatwave. As a lethally hot sun rises one morning, your fictional Frank May walks out onto the street:

Every building had a clutch of desperate mourners in its entryway, waiting for ambulance or hearse. As with coughing, it was too hot to wail very much. It felt dangerous even to talk, one would overheat. And what was there to say anyway? It was too hot to think. Still people approached him. Please sir, help sir.

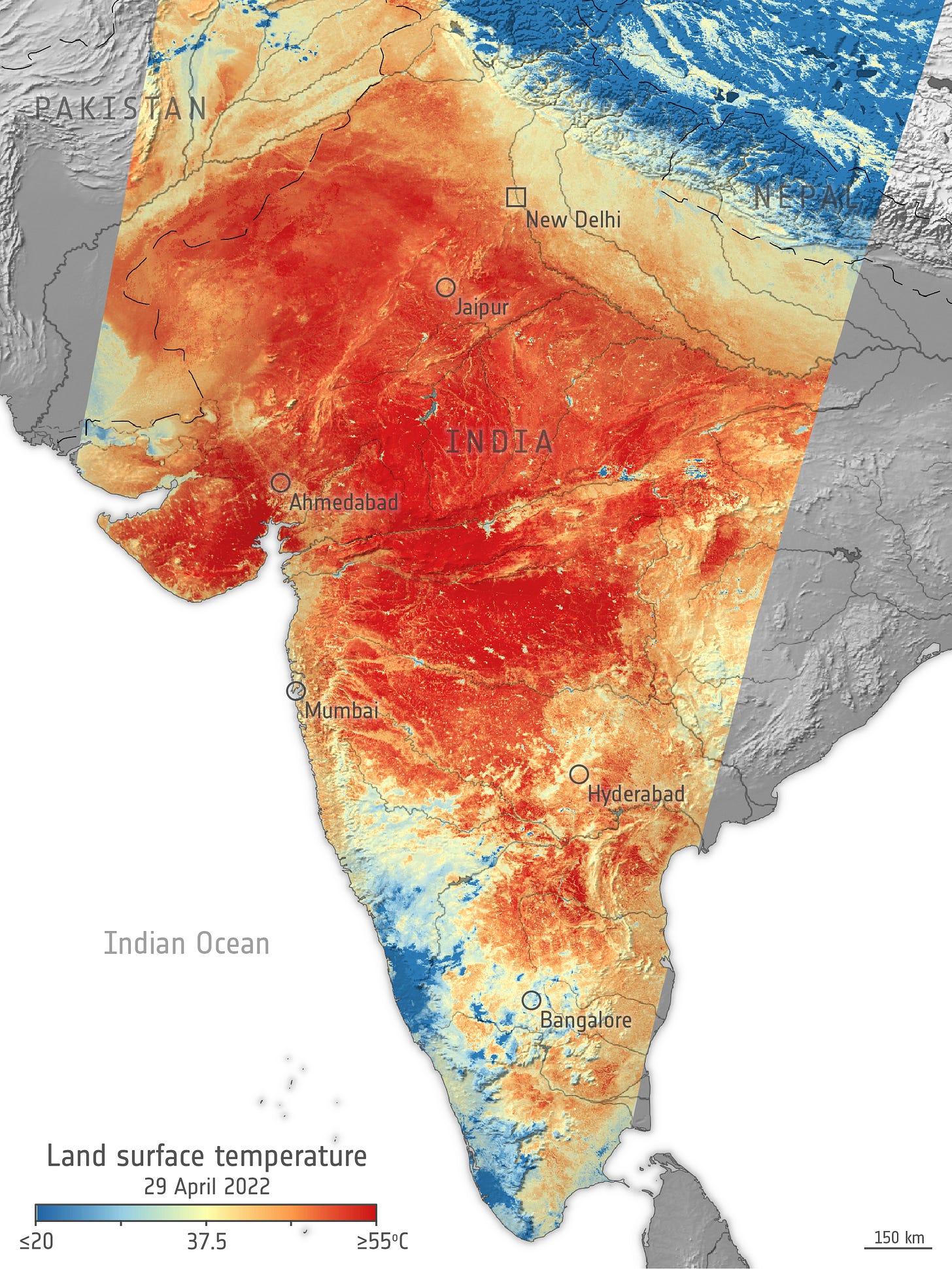

At the time I was turning these pages, a devastating, lethal heatwave was hitting India and Pakistan. In the year I read your novel, scientists estimate the number of heat-related deaths in Europe’s summer at over 60, 000. Deaths due to heat in India are likely well under-estimated. In June this year 50 people died in a week in a heatwave in India, with public health experts stating heat-related deaths in India are very much undercounted.

2022 Indian heatwave: data from Copernicus Sentinel

How does it feel to survive the horrors of a climate disaster? Your character Frank struggles with PTSD. We see him in therapy, we see him breakdown, we see him struggling with what constitutes ethical action in face of a world where we continue to roll on towards climate breakdown. How do you face each day with this knowledge?

We have people like Frank now amongst us - the survivors of the Black Summer bushfires, or of the Lismore floods. Your fictional character is so close to home. Frank comes good - through making human connections, and working for climate refugees.

What would it be like to take head up a UN Ministry tasked with:

defending all living creatures present and future who cannot speak for themselves, by promoting their legal standing and physical protection.

Your fictional character Mary Murphy shows what real climate leadership can look like. She is a ‘climate changer’, as Tim Flannery would say.

I heard your message, loud and clear, that the climate future is already here. And that we have to understand the urgency of the relationship between today and tomorrow. Two white male billionaires recently did their best to distract us from the present dangers of global warming. In his interview with Trump on his X platform, Elon Musk not only underestimated the current levels of CO2 in our atmosphere - Musk used the levels recorded over a decade ago (400 ppm), but we are now into the early 420s ppm - he also suggested we have plenty of time. We don’t need to start worrying until we get to around 1000 ppm of CO2, when he gets a bit hard to breathe and you get headaches and nausea, according to Musk. Environmental scientist and climate warrior Bill McKibben called this the ‘dumbest conversation of all time’.

Your book is populated by so many active people working for climate - bureaucrats, scientists (trying to remediate the melting of polar ice), and eventually even bankers, who are central to reframing finance away from dirty fossil fuels to mechanisms like ‘carbon currencies’ which financially reward reducing climate pollution and supporting renewable energies. The book immersed me in so many conversations about climate, and so many ideas about how to move the world past our still very dirty carbon burning lives. I think about these characters every day.

As you shifted my relationship to time, the flow on effect was to change my relationship to space. My view of travel has been completely upended. Since reading your book I’ve given up international conference travel, and I’m trying to reduce my reliance of flying domestically by taking trains to visit family interstate. Flying causes climate pollution, and there’s no way around this reality. It creates a burden on the future - and in your book I met some of the people who will deal with the climate burden of my generation. As Mary says: ‘I’d like to spend more time on the ground … just stay in one place for a while, see what happens’.

Climate resilience

I didn’t want to read your novel because I worried it would make the future too overwhelming. It would be too existential, and bring me more anxiety than I could manage. But because of who the giver was, I had to read your book.

And the beautiful irony is it had the opposite effect on me. It helped me develop climate resilience. It gave me the courage and psychical strength to start writing on language in the climate crisis. I think this resilience came partly from getting to know some people from the future - but also undoubtedly from the multiple voices in the text. Voices of people who care so deeply about the planet and about humanity.

And I think it was helpful because it is fiction. Your fiction is very close to current experiences of course, but as fiction it is a profound act of imagination. And imagination is the crucial ingredient for seeing how the future can be different. Mary Murphy, now retired, ends your novel in a burgeoning romance. It’s a beautiful Zurich evening, the city alive celebrating Fasnacht, and Mary walks arm in arm with her new beau. And she thinks:

We will keep going, she said to him in her head - to everyone she knew or had ever known, all those people in her head - to everyone she knew or had ever known, all those people so tangled inside her, living or dead, we will keep going, she reassured them, but mostly herself, if she could; we will keep going, we will keep going, because there is no such thing as fate. Because we never really come to the end.

Thank you Stan. I am so grateful.

#WriteAWriter

Look out for other #WriteAWriter letters on Substack from Jodi Wilson at Practicing Simplicity, Brittney Rigby’s Top Shelf, and Sanam Mahar at notes from a work in progress. I’d love to hear your comments on writers who’ve given you clarity about the whole shape of your life.

Loved to read this Annie ❤️❤️❤️

Beautiful writing Annabelle. I’m off to buy and read this book.